“If one hopes to live a long life then one can look back and think that so many years have passed, but I’ve done so much in the past 40 years. I’ve produced work, produced children, I keep working, I keep trying to live in the present, and staying healthy. I look to the future, actually. I don’t divide my life between past, future and present; I’m living and all of these ages are within me. I don’t turn my back on my past – I think about it, my childhood, my family. Many of my people are dead, and every day I think about my brother, my husband and my friends who are gone. Not so much with nostalgia or sentimentality but as a living part of me.”

“If one hopes to live a long life then one can look back and think that so many years have passed, but I’ve done so much in the past 40 years. I’ve produced work, produced children, I keep working, I keep trying to live in the present, and staying healthy. I look to the future, actually. I don’t divide my life between past, future and present; I’m living and all of these ages are within me. I don’t turn my back on my past – I think about it, my childhood, my family. Many of my people are dead, and every day I think about my brother, my husband and my friends who are gone. Not so much with nostalgia or sentimentality but as a living part of me.”

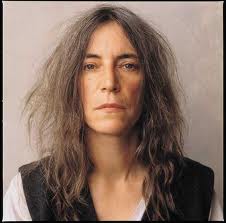

Patti Smith is talking from New York, where she has lived for over 15 years. She moved to NYC from Detroit after her husband, Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, and her brother, Todd, died within a short space of time of each other, and as she speaks about most things art-related, you can sense that loss emanates from her like a vapour trail. Yet she is steely, this woman; it would be wrong to define her as a survivor merely because of her age, yet there is that element of a life lived amidst turmoil, excitement, tragedy, adventure, art and fun. At 64, Smith remains a compelling figure, a rewarding artist, not least because she has been, throughout the decades, as much a pioneer as a participant. Ageing, however, is one of life’s great levellers – does she feel that the time to create more work is slipping away?

“No one knows how long he or she is going to live, you know,” she says in a casual why-are-you-asking-me-that? tone. “The poet Arthur Rimbaud lived to only 37; Robert Mapplethorpe lived to only 42. I’ve already outlived Jackson Pollack and John Coltrane. I think an artist can work their whole life, and if I’m lucky enough to live until I’m 90 maybe I’ll be like Picasso at work until the very end. My work ethic hasn’t changed throughout my life – I work just as hard and feel that my work has strong qualities. Thinking about how little time there is left is almost a waste of time; one could get depressed about it. Fate can decide for or against you, so I think, ultimately, one should just take care of themselves and see what happens.”

From her emergence in New York (via Chicago) in the late 60s/early 70s, when she hooked up with struggling artist/photographer Robert Mapplethorpe (whom in her extraordinarily elegant 2010 memoir, Just Kids, she describes as “the artist of my life”), Smith gradually made a name for herself as a willing partner to experimentation. Nothing was closed or alien to her: performance art, spoken word, painting, acting, rock journalism, singing – all these and more formed the backdrop to her virtually poverty-stricken New York life as friend, lover, co-conspirator and muse to artists such as Mapplethorpe, playwright/actor Sam Shepard, and Blue Oyster Cult’s Allen Lanier.

Yet it was as a singer/performer that she gained a high profile. It helped that she fitted the proto-punk look like a leather glove: a whippet-thin, stringent beauty that fused scarecrow chic, Keith Richards-like androgyny and arty poetry with intelligence, femininity and wit. Over the years, she has continued, more or less, fighting the good fight against the dumbing down of art as she blends rock’n’roll with poetry and vice versa. Not for nothing has she been described as “Rimbaud with Marshall amps.”

“Many people have done that beforehand,” Smith contends. “I’m in a line of artists that have worked to infuse rock’n’roll with poetry, the most important being, probably, Jim Morrison. Whatever work I’ve done, be it in rock’n’roll or poetry or activism or motherhood, I’ve tried to do well. Accolades? I don’t depend on them, I don’t work to receive them. If I get one I try to accept it in the spirit that it was given. If they think I’ve been an influence, or if they think my work has been of some avail, then that’s a nice thing, and I’m happy to be acknowledged.”

As a creative person, what does she think is her defining characteristic? “I like to work, and my defining characteristic is that I carry that with me all of the time. Work isn’t a compartment for me. Some people go to church on Sunday and the rest of the week they don’t think about religion. Some people pray every day and God is with them as they walk. My creative impulses are with me always. I would do it whether or not it was accepted, desired or praised. When I was married I lived in Detroit in almost total obscurity, and I worked just as hard.”

Weaving in and out of public consciousness through the years has meant that, while revered by many heavy-hitters (the list includes Michael Stipe, Bono, Johnny Depp, Lou Reed, Morrissey, Shirley Manson), there are thousands more that aren’t fully aware of what Smith does, who she is. This changed somewhat last year with the US National Book Award-winning Just Kids, a graceful fusion of love story and elegy, a salute to NYC and a celebration of her time with Mapplethorpe in ropey, pre-fame days when food and books were stolen for varying types of sustenance. Was it a therapeutic book to write?

“No, it wasn’t,” is Smith’s straightforward reply. “It was a difficult book to write because I had to write it intermittently, I kept putting it away for very long periods of time. If I hadn’t promised Robert I’d write it, I’m not so sure I would have written it at all. So therapeutic, no, but what it did do was accomplish a mission, and when we do that we have a certain satisfaction of having kept a promise and honouring it. The greater satisfaction, however, is that people seemed to have, through the book, a better understanding of Robert. That was my primary focus – that knowledge of him is not just filtered through other details that are either negative, exaggerated or imagined. The book gives the reader a more holistic picture of him, and that makes me happy.”

(This article first appeared in The Irish Times/Ticket, July 2011.)