Little problems, says Paddy McAloon, arise to put a kink in your day. The mid-50s lead everything of Prefab Sprout knows what he’s talking about, and if it wasn’t for the fact that great music is still being made, then you would direct an unsightly and admonishing finger towards the Gods for having the nerve to encumber McAloon with not one but two sensory afflictions: severe tinnitus and detached retinas.

Little problems, says Paddy McAloon, arise to put a kink in your day. The mid-50s lead everything of Prefab Sprout knows what he’s talking about, and if it wasn’t for the fact that great music is still being made, then you would direct an unsightly and admonishing finger towards the Gods for having the nerve to encumber McAloon with not one but two sensory afflictions: severe tinnitus and detached retinas.

“I can see better than I could a few years ago,” he relates, “but because I’ve had cataracts removed from both eyes what happens is that you can’t focus on things that are close to you without a different pair of glasses. I always have those glasses with me, but most of my days I carry around a big magnifying glass, which means I feel like an old git. The care and ease with which most of us go about our business is gone, but let’s be honest, compared to many other people it’s a minor complaint.”

How do these health problems affect his work? They’re not too useful in a studio, surely? “I can’t see the end of big mixing desks, so I tend to use small equipment. I work by myself because I feel that I would try the patience of people around me. You might think that given the circumstances of my ailments it would be much better to have someone who can see and hear properly to help me, but in a strange way I feel slightly embarrassed and would rather proceed quietly and in a solitary manner.”

Proceed quietly in a solitary manner? Now there’s a modus operandi for artists to take note of. When you’re as admired a songwriter as McAloon, however, whatever way works for him is good for us. For some, Prefab Sprout might just be an obscure band with a silly name from the 80s, but fans have stuck with the sophisticated pop albums from that decade (including Swoon, Steve McQueen), the 90s (including Jordan: the Comeback, Andromeda Heights) and the Noughties (Let’s Change the World with Music), smug in the knowledge that they backed a winner.

Fans also backed a maverick, albeit one whose musical and lyrical motifs referenced Sondheim and Bacharach instead of the prevailing 80s moods of Morrissey, Weller and Costello. And so between lengthy gaps from album to album – as well as the news that McAloon’s health issues had effectively sequestered him in his home studios in the North of England – fans could do what fans could only do: resign themselves to bouts of respectful thumb-twiddling until McAloon felt like striking again.

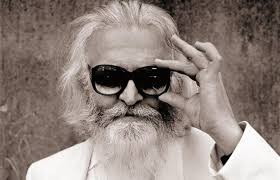

Which brings us to Crimson/Red. By name it’s a Prefab Sprout album, but in actuality it’s McAloon solo throughout. Inevitably, as the years passed, Chinese whispers were more clearly heard – of his reclusive nature, of his current state of genius, of his tendency to lock himself away for days on end to create, of his long silver beard and even longer silver hair. McAloon giggles all the way from here to Durham, which he lives close to with his wife and three daughters; he is amused by the relentless grinding of the rumour mill. “The reclusive thing?” He half-sighs, half-smiles. “I know I’m supposed to shrug this tag off, and say things like ‘no, no, no, I’m out there all of the time’ – and I am out quite a bit – but the notion of joining in has never been me. I put a brave face on it in the 80s and 90s, and it was easy for me to go along with it, but deep down I’ve always enjoyed myself more when the band was hypothetical and when the next album was, theoretically, in my head. When it came down to actually doing it – the joining in, I mean – it wasn’t that it was too much like hard work, but you would come up against your limitations.”

Such as? “That the voice isn’t quite as good as you’d like it to be, and that the songs aren’t quite as good, either. All of that stuff. So apart from the health issues, the reclusive thing is maybe my attempt to get closer to the source of what I think is good about what I do. Because that’s what I do now – I write all of the time. I’m always working on something or other, and when or if it gets recorded is secondary. The joy of it is consistently liking the mystery of what a song is, where you might find it, and how good it might be. That’s me.”

It might surprise some to know that, even after 30 years of making albums that have, by and large, always been critically acclaimed (and which, particularly in the 80s, sold millions, making Prefab Sprout unlikely, unwilling pop stars), McAloon continues with this pursuit. The mystery of what constitutes a song? What a wonderfully quaint notion for a mildly eccentric songwriter in his mid-50s to still have. “Yes, it is, isn’t it? That isn’t always the case for some people, but for me I suspect it’s not even on the level of some grand artistic quest. I would like to think it is just that, but I guess – and I’m not sure I like to say this – it’s probably more behavioral, perhaps some kind of obsessive compulsive thing. I recall that as a teenager writing songs there was, literally, a thrill that came out of such creativity. I feel it’s more to do with who I am than obsessiveness; working the way I do makes me feel the day has purpose and shape if I have made something that makes me stand out of myself.”

Chasing the mystery can fade away, of course, and for some people what they do becomes little more than a greatest hits package. “There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not the driving engine for me. Some people – in order to put me into context for 16 year olds, I’d imagine – describe me as an 80s guy, but to be quite honest I think I’m sharper and more engaged than that description. I’m much more on the ball, which I hope doesn’t sound like a daft thing to say.”

All songwriters have their habitual topics and narrative motifs, and while McAloon could arguably be termed a post-feminist songwriter (“The 70s manner of writing about lust and love was done in a very bravado-like way, but whether by temperament or genetic design, I always found that to be fake – or you had to be Led Zeppelin, who could always pull that kind of thing off.”) he could just as easily be congratulated for daring to be anti-cliché. Tellingly, he says he doesn’t share much of his time for contemporary pop music. The implication is that, as both former acclaimed pop star and consistently praised songwriter, McAloon knows all of the tricks. The inference, meanwhile, is that pop music is fundamentally no more and no less than the shuffling around of a few elements with similar chord changes, and coming up with lyrical themes that don’t stray too far from either romance or disappointment.

We detect a wry smile coming our way. Romance? Disappointment? For Paddy McAloon, these are tasty, often touchy topics. “I have a song called My Mysterious Power Over Women, which has a line ‘where does it come from and why is it so?’. My wife and myself were out one day, buying school uniforms for one of our girls, who was with us. I came into the shop ten minutes after them, and in the shop a kindly lady brought over a chair for me. Having a long beard and long silver hair might be asking for it, but it made me giggle.”

One of pop music’s truly gifted souls pauses to consider something. “There’s a Martin Amis phrase about men no longer snagging on the DNA of women.” McAloon bursts out laughing. “That’s me, that is. Yeah, welcome to your 50s, pal!”

(This first appeared in The Irish Times, October 22nd, 2013.)