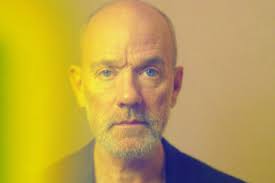

Michael Stipe is looking, as usual, pensive. As slim as a pencil, he sports (actually, that’s hardly the word – there is nothing remotely sporty about Michael Stipe) a salt and pepper stubble beard that shades in his countenance; a continuous supply of match-thin roll your own cigarettes and a takeaway mug of coffee are the orders of the day. We’re sitting on a park bench in Dublin’s Marley Park, slowly broiling under the moderate heat of the midday sun. Stipe and his cohorts – REM guitarist Peter Buck and bassist Mike Mills – have just completed the soundcheck for their open-air concert at the natural venue.

Michael Stipe is looking, as usual, pensive. As slim as a pencil, he sports (actually, that’s hardly the word – there is nothing remotely sporty about Michael Stipe) a salt and pepper stubble beard that shades in his countenance; a continuous supply of match-thin roll your own cigarettes and a takeaway mug of coffee are the orders of the day. We’re sitting on a park bench in Dublin’s Marley Park, slowly broiling under the moderate heat of the midday sun. Stipe and his cohorts – REM guitarist Peter Buck and bassist Mike Mills – have just completed the soundcheck for their open-air concert at the natural venue.

The band has also completed the listing for its second official Greatest Hits album (In Time – Best of REM 1988-2003, which marks their major label years with Warner Music from 1988’s Green to new songs Bad Day and Animal), and Stipe is, therefore, in a particularly reflective mood. As rock stars go, Stipe is the most courtly, respectful and intelligent one is likely to meet. Over the years, he has been branded as one of rock’s most inscrutable and abstract major players, but as he has gotten older (he’s now over 40) it seems the enigma code he once transmitted has been deciphered and broken down into accessible chunks of conversation. With a new album more or less ready to go for the first quarter of 2004, Stipe talks about the In Time… collection as if it’s the closing of a chapter, with the forthcoming studio release as the opening of a new one. Both appear true.

“People keep calling me on the putting out of In Time… like it’s some monumental message we’re sending out to our fans,” explains Stipe, his forehead shining, his long fingers playing with Rizla papers. “The fact is we simply haven’t done it before, and the Lord knows we’ve been around long enough. We should have pulled it together before… Personally – and I think I can talk for Peter and Mike as well – it just feels like closure in a way. We are solidly a trio and we’ve moved into that phase of this particular journey we’re on. And we had the confidence to go back to Bill (Berry, REM’s former drummer who quit in 1997) and ask him was he cool with it. He was. We said, right, let’s shut the door.”

When REM first made their presence felt in the early-mid 1980s, it was through their hybrid Byrds/Who/folksy sound. Distinctive in a way that other bands were depressingly familiar, Stipe’s oblique lyrics were lifted out of inaudibility by Buck’s chiming guitars and the gear shifting, driving rhythm section of Mills/Berry. Their debut album proper, 1983’s Murmur, was accorded Album of the Year status by Rolling Stone; when the band signed to major label Warners in 1987, the following year’s Green took them out of cult fandom (populated by so-called ‘distiples’) and propelled them towards the kind of fame reached only by a few. Subsequent records – particularly the mid-late ’90s releases New Adventures In Hi-Fi, Up, and 2001’s Reveal – have seen a shift towards a level of experimentalism that cost them a sizeable portion of their commercial fan base. Yet REM seem unequivocally resolute in their determination to proceed as unplanned.

“I look back on the amount of songs we’ve written and it doesn’t seem like very much,” says Stipe. “Personally, I see my adult life marked by albums and tours. There is other stuff going on, of course, but albums are the markers for me, the milestones whereby I can remember dodgy haircuts and when I was wrapped up in a terrible passive/aggressive relationship with a horrible person; or that’s when I lost my mind and things weren’t going so well; or, when I was questioning my own belief system and searching for a new one. Blah, blah, blah… All those things that we go through in our 20s and 30s; then you look back on it and it all seems rosy-hued, but nevertheless something you would not want to go back to on any level.”

Age does not seem to have dimmed his vision or dampened his enthusiasm, either. He’s been thinking of the ageing process recently, he says, cross-referencing his own years (43) with those of his band’s pesky teenage fans. “Being in your 40s is great. What 18-year-olds have that someone of my age doesn’t are great skin, great teeth, great hair, a psychotic sense of self and an insane love of sex. I would say I have probably maintained and kept the sense of self and the sex thing. And the innocence – I haven’t let go of that at all. It’s now not quite as blinkered as it was when I was 22 or 23; the things that I’ve learned I’ve learned well, and maybe the most important thing I’ve learned is to forever challenge the things I think I know and have learned. What a teenager has over everything is a sense of immortality and a cherishable innocence about what the present and what the future is. That’s what they have over someone of my age. What I have over them is that I was once a teenager and so I know what that feels like – if I’m smart enough.”

The decline in REM’s commercial sales is something that appears not to concern Stipe and co. Stating that radio is in a quality decline, he says that attaining the band’s erstwhile immense level of success once more isn’t part of any strategic gameplan. “We’d sooner make the music we want to make than anything else. If the world happens to be in step with that, then great, I’m all for it – I love that ridiculous level of celebrity and recognition. Are we going to change what we do to attain that? No.”

Such a sense of integrity is rare in anything these days. Mention this to Stipe and he says he’s complimented by it, that he despises false modesty. “I know what I’ve done and I’m proud of it, but it’s not for me to apply integrity to what I’ve done. Other people, however, have done that in spades and – hey – I’m okay with it!”

Rather than growing into its own skin over the past 20 years, inhabiting their body of work, REM come across as somewhat more reptilian – they shed their skin and keep metamorphosing into different things. A residue of what has been as well as internal cross-referencing remains, but by and large REM continue to change. “Perhaps the changes are more dramatic for me,” says Stipe, “because I’m more in the middle of it than a listening audience. In fact, it was only about five years ago that I realised my voice was quite recognisable. I never got it until then that six or seven other singers in other bands didn’t sound just like me. So when I think we’re making monumental leaps, listeners who are fans or who are familiar with the music – or even people that don’t like us – might just say, oh, it’s REM again, that voice and that guitar sound.”

In their 23 years as a band, Stipe argues, out of 13 studio records there are less than two albums worth of songs he would choose as being of value. “And they’re recorded songs. For me the live versions, occasionally, are more real. In the studio, you try the best you can to make them great – of the moment, not just for you but something you can listen to over and over again – but I’ve failed to capture that moment from time to time on some really good material. There it is. But in a liiiiiiivve setting some of those same songs really blossom. Songs such as Lotus, Country Feedback, E Bow The Letter, Losing My Religion and Man On The Moon would definitely be on the iPod I would take through a black hole into some ulterior universe. If someone there asked me what did I do with my life, I would play them these songs and say, this is music, that’s my voice and these are my thoughts.”

Ulterior universes notwithstanding, the sense of REM staying true to itself persists. Has there ever been a temptation to stray? “Temptation is a lovely creature and a shape-shifter, and the first example I can think of is the untold millions that were thrown at us by Microsoft to use a song of ours for one of their commercials. To take the money and run for the use of a song that was going to be on television in an ad for six months was pretty strong.”

REM didn’t do it and “I’m really glad we didn’t,” Stipe states. “What stopped us? It just wasn’t right. Music is when I kiss the ring. Music is too… Is the word ‘holy’ too powerful? What can I say? It’s my church and that’s that…”

(This first appeared in The Irish Times/The Ticket 2003.)