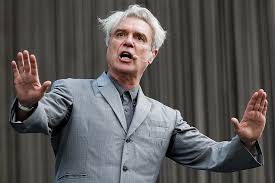

Brooklyn, June 29: David Byrne is on precious downtime, but he’s still eager to talk in his um-er-oh-maybe-I guess manner; it’s the verbal shorthand for what makes his nervous tics tick, but it’s so ineffably David Byrne it’s almost endearing (except when they go on to deliberate amongst themselves, that is; then it becomes finger-tapping tedious).

Brooklyn, June 29: David Byrne is on precious downtime, but he’s still eager to talk in his um-er-oh-maybe-I guess manner; it’s the verbal shorthand for what makes his nervous tics tick, but it’s so ineffably David Byrne it’s almost endearing (except when they go on to deliberate amongst themselves, that is; then it becomes finger-tapping tedious).

His time is precious these days, he says; he’s so much busier now than he has ever been and his vacations are forced ones. After he plays a couple of gigs in Ireland at the end of July, he plans to take himself and his young daughter to Spain. “I have to be away from messages and emails, but I can always write songs, so I just bring along a guitar – it’s easy to focus on that in remote places.” Remote places seem to be natural territory for David Byrne; it’s fairly obvious that he’s been asking himself the same question – ‘how did I get here?’ – for quite some time now.

Born in Dumbarton, Scotland, he moved to Baltimore, Ohio as a child. Graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design, Byrne eventually abandoned his training in visual and conceptual arts in favour of music and New York’s nascent art/punk rock scene. Within a few years, Talking Heads – the band Byrne formed with fellow Rhode Island students Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth – were lauded as one of the best American bands of the 70s.

Inventive, witty, ambitious and unorthodox, Talking Heads sailed through punk, post-punk, new wave and beyond to become a pop band that epitomised the word ‘intriguing’. Come the early ’90s, Byrne’s side projects – which included a collaboration with Brian Eno on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a soundtrack to Twyla Tharp’s modern ballet The Catherine Wheel, a movie, True Stories, further collaborations with playwright Robert Wilson and Ryuichi Sakamoto, experiments with Latin-American and European orchestral music and the setting up of his world music label Luaka Bop – clearly spelled the end of Talking Heads.

Throughout the ’90s and up to the present day, Byrne has continued to expand his artistic palette; his recently released album, Grown Backwards, even has him tackling Bizet and Verdi tunes with some success. For someone who has a reputation for being the smartest clever person on the block, he’s certainly not backward in coming forward with bright, accessible ideas. You might think working in an industry where he has to compete with people for whom a banal pop song is the peak of their achievements is a trial. Not so.

“I think some of the banal stuff is incredibly well done. It can be clever or equally smart, but in a more commercial way that I sometimes envy. I envy it because often it’s really successful. A simple pop song can be a work of absolute genius; there are certain kinds of pop music I can’t do, and other times are there kinds that I stumble on. I’ve been doing it long enough, so I feel I have enough instincts to know that every once in a while I’m going to do something that connects with people.”

Over the years, Byrne has become the type of intelligent pop artist that has managed to escape from the constrictive nature of the commercial side of the music industry, all the while embracing different forms of music that have little connection with Top 20 pop music. There is music, he says, he hasn’t dealt with yet and areas he feels he hasn’t explored fully or in a better way. There are, he imparts to a background noise of a Brooklyn street, always further avenues to explore. “It’s fulfilling creatively in at least attempting these forms of music. And especially so when it seems to be working. When it doesn’t I get kind of lost.”

Yet Bryne’s success rate, artistically as well as commercially, means that he’s rarely left floundering. He says he has had to become more organised as the years have passed, primarily because of the demands on his time. “Funny how that happens,” he ponders, allowing his trademark 20-second gap to create the impression of thoughts thoroughly lost in transmission. “You’d have thought when Talking Heads were at the peak of their popularity that I would have had to set aside time for songwriting – which I did. But I guess I have more varied irons in the fire at the moment. Other people do it as well, of course, and it’s all the same process. The thinking, techniques and craft are different, but the process is quite similar. And the end results, to me at least, merit the same judgements. To others, perhaps not.”

Ask Byrne about his unique selling points as an artist – what parts he can reach that others can’t – and he emits a surprisingly hearty laugh, as if it’s something he hasn’t thought of before, the question a hefty punchline to the seriousness of his career to date. “I think when I succeed I can sometimes write something that has a certain amount of familiarity but that also has a certain level of surprise – something that takes you a little bit out of the ordinary. The same might be true lyrically, in that sometimes when it works it appears I’m dealing with things that resonate with people. But I’m also, perhaps, saying something that hasn’t been said or hasn’t been said in quite that way before. For me, that’s when it works. How much does it work? I’m not sure what the percentage is – I guess the odds are all right, though.”

Success, of course, is relative. Alone of his New York mid-’70s contemporaries, Byrne has been astute enough not to rehash memories or reform a once commercially popular band for the benefit of the AOR nostalgia/summer crowd circuit – it’s simply unthinkable, for example, that a regrouped Talking Heads would ever play, say, Killarney (or, indeed, that they would ever reform). Rather, several Talking Heads songs now form part of Byrne’s far wider repertoire – the majority of which is culled from his cohesive and imaginative solo work. One wonders which time, place and music – way back when or more recently – David Byrne would prefer.

“Naturally I’m going to say now because I don’t have a lot of choice in the matter. If I did have a choice? Well, I’m a slightly happier person now; I think my writing is better than it used to be – it’s certainly different. I did realise recently, going over some old unused lyrics, there are certain things I wrote that I could never get my head into again. I’ve undoubtedly changed as a person and once the time has passed you’re never going to write that kind of thing again. But it’s good I did it when I did it.”

Does Talking Heads seem a lifetime away? “Yes, it does seem a while back,” Byrne avers. “But I still deal with it. Even this morning, I was dealing with artwork for a new compilation album that’s coming out later. Most of the time the band is an abstract part of my past. That said, it’s not like it’s a faded photo, the band is actually pretty hard to forget. Sometimes I walk into a bar and a song is playing and I think it sounds oddly close and familiar. And sometimes I don’t recognise the Talking Heads song straight away. It could be another band, actually. Sometimes I hear it like that – a band that I have a strange, intimate connection with, but that is still intrinsically the band and me.”

The connection seeps into his solo music, of course, because the creator is the same. Yet still Byrne continues to surprise and enlighten; and to prove to people it’s possible to achieve a high level of success without compromising artistic vision. His latest album, Grown Backwards, for instance, hits the slightly esoteric spot with its mixture of post 9/11 rumblings, veiled comments on the Bush administration and arias by Verdi and Bizet.

“It was a surprise for me to do that, too,” he admits. “I tried it because I wanted to keep myself a little on the edge; opera is an area I wasn’t quite familiar with and I confess I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I like to stay focused! I reckon what has kept me doing for so long is that I don’t think of music as a marketing commodity.”

(This first appeared in The Irish Times/The Ticket, 2004.)