Here’s a question for you: given the choice between the carefully crafted, historically imbued and Viennese-style elegance of Café Gerbeaud and the everything-and-the-kitchen-sink, Mad Max, punk rock-style demeanor of Szimpla Kertmozi Café, in which one would you choose to nurse a coffee while either gazing into the distance, avoiding eye contact, reading a magazine or tapping away at a laptop?

The answer is not as easy as you might think, and for that you can thank Budapest’s long-standing, beguiling relationship with coffee culture. In Café Gerbeaud (Vörösmarty tér 7), for instance, you are instantly transported back in time. Founded in 1858 by Henrik Kugler during the good old days of the Austro-Hungarian empire, the flavor of history rises in tandem with the combined aroma of coffee and the herb/sugar whiff of the establishment’s famous szilvás lepény (moist plum pies). By comparison to the classical simplicity of Café Gerbeaud, Szimpla Kertmozi Café (Kazinczy útca 14) is a ripped and torn riot of influences. So: Café Gerbeaud and Strauss, or Szimpla Kertmozi Café and Sex Pistols?

It is apt that you are faced with such a conundrum in a city whose name is also divided: Buda (the historical half of the city on the west bank of River Danube) and Pest (the more commercial half on the east bank). But, then, that’s Budapest for you; its title aside, it’s a city that doesn’t do things by halves.

It’s important to note, however, that coffee culture has been integral to the city for hundreds of years, while the city itself has been home to coffee and/or café culture before anywhere else in Europe. What have the Turks ever done for us, you might ask in your best Monty Python accent? Well, when the Turks invaded Buda in 1541, the Ottoman Empire introduced the initially bitter product to its occupied populace, and as the years passed by so coffee’s pleasurably addictive qualities set in. By the end of the 19th century, the coffee houses of Budapest (Buda and Pest amalgamated in 1873) were places where artists, intellectuals and other freethinkers gathered to discuss, debate, gossip and generally plan their lives and the lives of others. In fact, such was the symbiotic social relationship between cafés and artists that the latter would have continuously reserved tables; then, unlike now, struggling, penurious artists would spend most of their days in their usual coffee haunts, which would recognise such regular custom by providing writing and sketching materials.

From 1910 to the 1930s, coffee culture prevailed, as over 500 cafés around the city hosted, essentially, social parlour gatherings, where the smart ones and the not-so-clever types mingled together in one big convivial melting pot. Such halcyon days were not to last, however, as World War 2 and the subsequent takeover of Hungary by the Communist regime (which regarded Budapest’s cafés as gathering points for underground, resurgent groups hell bent on forging plans to overthrow or undermine the administration) brought to an end the majority of these coffee houses by closing them down. And that, unfortunately, was that until 1989, when Hungary opened its borders with Austria, which in doing so brought about the collapse of the Soviet Union. Happier times, then, and while it took some years for Budapest’s classic cafés to once again look their best (the cafés had been closed down, not torn down), it’s true to say that, in line with, perhaps, Vienna, the city boasts more beautiful cafés than anywhere else in Europe, if not the world.

Which brings us back to the likes of Café Gerbeaud, which was founded on the back of Henrik Kugler’s background in confectionary studies. In the 19th century, Café Gerbeaud was considered the best of its kind in Budapest; it made, prepared and sold all manner of dainty, exquisite treats from as far afield as Russia and China, as well as Kugler’s house specialties such as singular liqueurs, sugar bon-bons and creamy, foamy coffee with a liberal sprinkling of chocolate. Today, it still looks as if time hasn’t passed: the ceilings are decorated with Louis XIV-style rococo stucco, and the chandeliers and the wall-lamp fixtures are in the style of Maria Therese of Austria.

A rather less imposing but no less historically interesting coffee house is Central Kávéház (Károlyi Mihály útca 9), which is another of the great coffee houses of Budapest, and at one period of time a true hub for progressive thinking – an open university, if you will, for the city’s artistic fraternity and student population. It has experienced turmoil through the years, however. Established in 1887, it could boast to have been the training ground for Hungarian radical and literary journalism by allowing various newspapers and periodicals to be edited on its premises. It closed down during the two World Wars, while in 1949 – Hungary’s year of nationalization – it was turned into a canteen for construction workers. In the 60s, it became university social club, and in the 90s was used as an amusement arcade. Latterly, it was been restored to its functional, one might say its utilitarian past, and it’s a great place to sit at one of its marble tables, sip from a gourmet coffee, pick at a delicious Dobos cake, and watch the people of Budapest go slowly by, from flirting students to elderly ladies setting the world to rights.

If you’re looking for something a tad more elegant – more cultivated and decoratively poised, perhaps, than even Café Gerbeaud – then make a beeline for New York Café (Erzsébet körút 9-11) at the New York Palace Hotel (originally the offices of the New York Life Insurance Company). It opened in 1894, and was instantly dubbed the most beautiful café in the world. It is a description that many would say it retains. While the building itself is redolent of the Italian renaissance and baroque periods (complete with 16 windows that are adorned with individual “El Ashmodai”, diabolic figurines, designed by Károly Senyey, that signify a blend of coffee and meditation), the lavish interior is astonishing. Marble, bronze, velvet, silk, panel paintings and Venetian chandeliers combine with a noticeable scent of moneyed clientele (the building underwent full refurbishment from 2001-2006 by the Italian Boscolo luxury hotel group) to produce a café/restaurant that has to be seen to be believed.

Fancy something a bit more down to earth but just as “landmark”? Then perhaps Müvész Café (Andrássy út 29) will do the trick. Diagonally across from the State Opera House, this is as close to an authentic 19th-century grand salon-style establishment as you’ll ever see. It survived the Communist period pretty much intact (possibly because it had less airs and graces than other city coffee houses), and because of that its interior is a wonder of virtually discontinued design: high ceilings, stately chandeliers, beautifully crafted marble tables, a wrap-around counter and magnificent banquettes. Müvész Café has, however, an added bonus up its coffee-coloured sleeve: it has every so slightly modernised its business strategy (disliked by some, it has to be noted) by employing weekend DJs to supply a low-key soundtrack of old-school and contemporary ambient/electronica music. A range of good, strong coffee options, cakes and tarts, and music from the likes of Neu, Cluster, Fourtet and Grasscut? What’s not to seriously love about that?

Indeed, what’s not to love about Gerloczy Café (Gerlóczy utca 1), either? While it may not have the acute sense of history of other similar city establishments, it is located on a calm, leafy square tucked behind Váci utca (which is a good street for shopping, by the way), and could be confused for a bona fide Parisian bistro. In fact, when director Steven Spielberg effectively annexed the city in 2005 for his film Munich, Gerloczy Café doubled as one; so it’s more European by design, maybe, than strictly Hungarian, a stance typified by its menu, which is somewhat more international-based.

Did we say European by design? Strike that in terms of Café Menza (Liszt Ferenc tér 2), which is so deliberately retro in terms of its compositional likeness to Soviet-style canteens (rigid geometrical lines stretched metro-map style across the walls in varying tones of orange and brown) that you’d expect nettle soup to be on the menu and copies of One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich to be distributed free on entry. It also might not help that the near-as-dammit English translation of “menza” is “cheap canteen”. Don’t be sidetracked by the design or the description, though; this place, literally seconds way from the implausibly appealing Oktogon Square, is quite likely the coolest modern eating/drinking place in the city, and the fact that it’s situated on bustling Lizst Ferenc tér means that if the weather is good al fresco dining/sipping is a merely a question of choice.

Which brings us back reasonably neatly to the question we asked at the start of this glimpse into Budapest coffee culture: which would you choose between the class of Café Gerbeaud and the clash of Szimpla Kertmozi Café? The answer really depends on what kind of mood you’re in and what time of the day you’re out and about. Are you looking for grand architecture or grunge atmosphere? Do you want strongly considered design or are you in the mood for a dose of dishevelment? Do you want to dress up or down? Do you want harmony or discord? Is it 12 noon or 12 midnight?

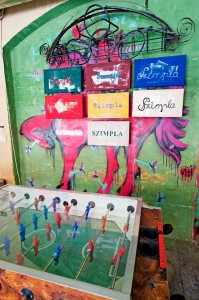

If it’s the latter half of these questions that you’re nodding to, then you’ve got to check out Szimpla Kertmozi, which is located in the back streets of District VII. It is, quite simply (or, er, szimpla?) the most unusual café/bar you will ever set eyes on. Employing a less-than-zero design sensibility, it is known, indigenously, as a “ruin bar”, which is wholly indicative of its mismatched chairs, tables and sofas, and its overall air of visual dissonance and disarray. The pitch is short and sweet: Szimpla Kertmozi is funky post-industrial getting it on with the chill-out zone in a Dystopian, alternate universe. Is it a dream as devised by Hieronymus Bosch? No. Is it a future-shock version of the kind of joint in which Blade Runner’s Deckard might meet a rogue replicant for an espresso before telling them their time had run out? Possibly.

Then again, perhaps it’s just an example of Budapest coffee culture in all its lop-sided, head-spinning glory. After which, frankly, it’s back down to earth with a visit to Gerbeaud or Gerloczy, and a cup of their finest.

(This first appeared in Cara Magazine, June 2010. All images copyright by Peter Matthews. TCL would like to thank Peter for his assistance and generosity with the images.)